Behind their homes is an oil pipeline and above them are high-voltage cables suspended between pylons. A little further off is a flare tower, burning off excess gas 24 hours a day.

Yet these potent symbols of Congo’s oil and gas bonanza mean little to the villagers who live in their shadow.

When darkness falls, they have to fire up a generator or light lamps. None of their homes has mains electricity.

“I’m 68 years old and I live in darkness,” said Florent Makosso, seated beneath a giant banana tree.

“My parents and grandparents had a better quality of life when it (Congo) was French Equatorial Africa.”

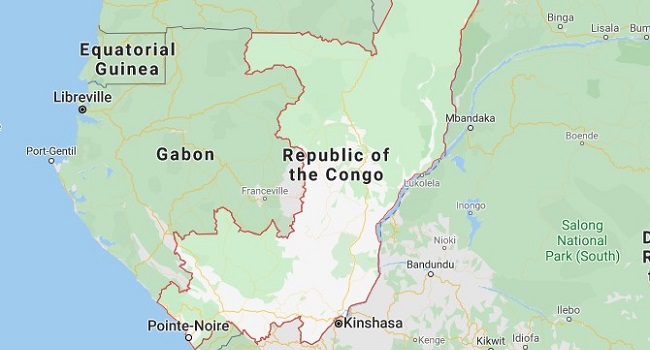

Makosso lives in Tchicanou, a small village 40 kilometres (25 miles) from Pointe-Noire — the energy hub of the Republic of Congo, also called Congo-Brazzaville.

The former French colony gained independence in 1958 and became a major oil producer some two decades later.

It notched up sales last year averaging 344,000 barrels a day, making it the third biggest exporter south of the Sahara after Angola and Nigeria.

The country is sitting on 100 billion cubic metres (3,500 billion cubic feet) of natural gas — more than the entire annual consumption of Germany, the world’s fourth-largest economy.

Marginalised

But little of this wealth has translated into prosperity for the country’s 5.5 million people — around half live in extreme poverty, according to World Bank figures.

Tchicanou is emblematic of a community that suffers the downsides of fossil fuels but gets few of its benefits.

Surrounded by fruit trees, the village of 700 souls straddles Highway 1, the lifeline between the Atlantic port of Pointe-Noire and the capital Brazzaville.

Tchicanou and the neighbouring village Bondi host pipelines and pylons for carrying oil products and electricity.

But they find themselves in the same situation as communities in the remotest parts of the country — they are still not hooked up to the national grid.

The village has no streetlights, and the biggest source of illumination comes from the flare tower at a nearby 487-megawatt gas-fired power plant, the country’s largest.

“It’s an ordeal living here,” said Makosso.

“We have to buy generators, which are expensive, and running them is a challenge in itself.”

Without power, “television and the other electrical appliances are just decoration,” he said, pointing to the simple challenge of keeping food refrigerated.

A fellow resident, Flodem Tchicaya, said Tchicanou “is in a good location. But the only use of the gas that they burn here is to cause pollution and make us sick.”

Inequality

Roger Dimina, 57, said that access to electricity in Congo was “unfair.”

“Instead of it starting at the bottom and heading to the top, it starts at the top and the bottom has nothing,” he said.

Across Congo, electrification in urban areas reaches less than 40 percent of homes, while in rural zones, it is less than one home in 10.

In a recent interview in the Depeches de Brazzaville, the capital’s sole daily newspaper, Energy Minister Emile Ouosso said the goal was to reach 50 percent by 2030.

A group close to the Catholic church, the Justice and Peace Commission, has been running an “electricity for all” campaign, focussing especially on villages in the orbit of Pointe-Noire.

The group’s deputy coordinator, Brice Makosso, said the government has declared a budget surplus of 700 billion CFA francs (more than a billion dollars) for 2022.

Just a small amount of this could hook villages up to the grid, he said, pointing to duties that oil companies in the area paid to the government.