Will General Khalifa Haftar get United States President Donald Trump embroiled in his first African war? The Africa Report takes an exclusive look at the future of the long-running conflict

By Jon Marks and John Hamilton

On a freezing day in Washington DC late last year, a veteran Libyan activist arrived in the United States (US) capital with a message for President-elect Donald Trump. His mission was to deliver both a plea and an explanation. The visitor wanted direct contact with the new president’s team – not via the State Department or the intelligence services – about what was happening in Libya and to ask the US for help.

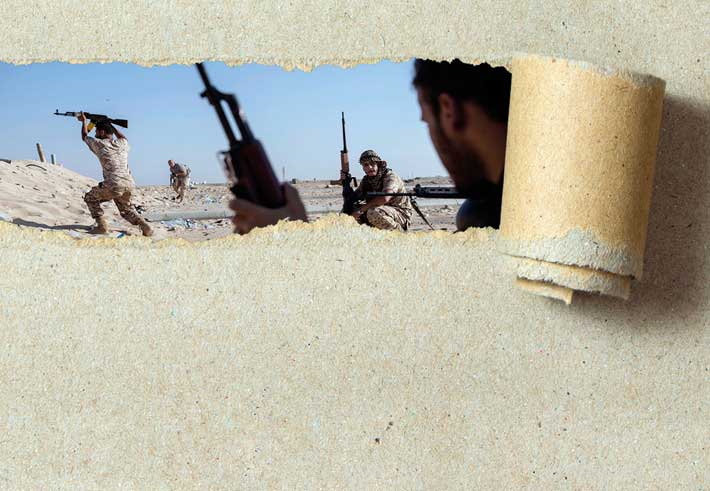

A former Islamist turned secular nationalist, the visitor was an envoy from Khalifa Haftar, the rogue general whose Libyan National Army (LNA) forces – which are backed by Egypt, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), France and now Russia – have been sweeping west across Libya. Haftar’s soldiers are now threatening to march on Tripoli, emboldened by their role, in tandem with a clutch of militias from Misrata, in driving out Islamic State (IS) rebels from the coastal city of Sirte in late 2016.

Some days later, a Washington insider told The Africa Report that Haftar’s message appeared to have got through to General Michael Flynn, Trump’s national security adviser, and his Africa adviser, Rob Townley, a former sergeant in the US Marine Corps and a national intelligence officer. What is less clear is how much sympathy Townley and Flynn, and, more importantly, President Trump, have for Haftar’s cause.

On the surface, Haftar would be an ideal ally for Trump: a fervent opponent of Islamist groups who is prepared to use maximum military force against them. And several European governments seem prepared to ignore Haftar’s brutal military tactics if he is able to reassert control over Libya’s seaboard and dramatically cut the migration routes across the Mediterranean.

Build A Wall

Such an approach could prove tragically short-sighted, argues Geoff Porter, a US expert on the region. “Both Trump and the Europeans have taken a ‘build a wall’ approach to policy rather than seeing the logic of promoting a deeper reconstruction of Libya,” Porter says. He warns that a low-level conflict in Libya could drag on for years based on “intervention light, in which missiles and special forces leave a light footprint, and the heavy lifting is done by local allies.”

Many Libyans share such forebodings as they see the regional alliance of Egypt and the UAE backing Haftar as a still more chaotic replay of the intervention to overthrow Muammar Gaddafi that split the country into warring provinces. The most pessimistic voices are predicting the demise of Libya as a national entity.

Haftar is an ally of some of Trump’s favourite people, notably Egypt’s President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi and Russia’s Vladimir Putin. Sisi and Putin have been stepping up their support for Haftar as the United Nations (UN)-backed Government of National Accord led by Fayez al-Sarraj in Tripoli looks increasingly beleaguered.

Islamist factions have encircled Sarraj and his ministers, and the international recognition of their government is all but worthless. The strongest Islamist group in Tripoli, led by Abdelhakim Belhadj, evidently wields more power than Sarraj.

But no one group has the muscle to enforce its writ in the capital and environs. Comparisons are odious, but the daily reality in Tripoli resembles something between Mogadishu and Aleppo.

Amidst the grinding conflict, Haftar presents himself as the strong man to stop the collapse. His long relationship with the US could appeal to Trump’s people. Haftar worked with the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) and lived near its headquarters in Langley, Virginia, for two decades. During that time, he hatched several plots to oust Gaddafi. They all failed, some at the cost of the lives of those that Gaddafi’s regime accused of involvement. Two of Haftar’s brothers were jailed.

The CIA-Haftar ties date back to the 1980s. Then, Haftar was leading Gaddafi’s expeditionary force fighting in Chad. He was then captured and detained in N’Djamena in 1987.

After meeting Chad’s President Hissène Habré, Haftar switched sides and set up a 2,000-strong force to overthrow Gaddafi. Three years later, Idris Déby, head of military intelligence and close to Gaddafi, overthrew Habré and vowed vengeance on all US stooges. Haftar and most of his soldiers were quickly flown out to Washington.

Washington’s Man

It was not until 2011, after the popular uprising against Gaddafi started, that Haftar returned to Libya. After Gaddafi was toppled, Haftar joined the National Transitional Council in Benghazi and was appointed army chief of staff. But his many rivals and the proliferating Islamist groups derided him as Washington’s man. Frustrated, Haftar returned to Virginia to bide his time.

With his eyes on the main prize, Haftar has fought IS forces and other Islamist groups when it suits him, using military and monetary backing from Egypt, Russia, the UAE and France to do so. Haftar already controls most of Libya’s eastern province of Cyrenaica and most of the country’s oil production. He is in alliance with the parliament in Tobruk and together they control the central bank in eastern Libya.

If Haftar is able to win backing from Trump’s administration as Russia steps up its support, he could become Libya’s most powerful warlord – with the aim of becoming its internationally recognised leader. But that is many kilometres down Libya’s dusty littoral. For now, Haftar is a factional leader – albeit one with powerful pals – threatening Sarraj’s UN-backed government in Tripoli. What Putin and then Trump decide to do could change all that.

Syrian Echoes

Mattia Toaldo, a Libya expert at the European Council on Foreign Relations, says: “Increasing Russian intervention is following the Syria playbook – starting with [Moscow’s] offers of intervention and then getting closer to Haftar […]. Today [18 January], there has been confirmation that Russian technicians will be on the ground and the revival of a $2bn arms deal from the Gaddafi era.”

Toaldo says he sees a real possibility of a dangerous escalation in fighting because of “a convergence … between Russia and Trump and Egypt – who are all going, as Haftar has put it, to root out all extremists.” Last November, a group of Russian technicians landed in Cyrenaica to help rebuild Haftar’s forces and upgrade their weapons systems. Since then, more Russian advisers have joined Haftar’s forces on the ground.

But ramping up powerful outside backing for Haftar could stoke a still-more devastating war in Libya rather than stabilise it. This time the conflict could be between Haftar and the Misrata militias, who were key to the overthrow of Gaddafi and now want their reward. Until late last year, IS’s occupation of Sirte, Gaddafi’s hometown, provided a buffer. IS was the common enemy of the other militias. With IS pushed out of Sirte, Haftar’s forces and the Misrata militias have already clashed three times this year.

British experts on the region are deeply sceptical about growing external support for Haftar. “Despots are two-a-penny, but enlightened despots are very rare,” points out Professor Toby Dodge of the London School of Economics. “Waiting for enlightened despots is not a policy.”

Crispin Blunt, chairman of the Foreign Affairs Select Committee at Westminster, dismisses the idea of backing Haftar and other authoritarians: “We have already tried that, and it didn’t work.”

Russia is a major arms supplier to Haftar, but it has to calibrate its involvement. A Tripoli-based observer says that Putin, although he has re-established Russia as a force in the region after its brutal military campaign in Syria, “wants to be seen as a bringer of stability and would like to expand Russia’s influence mostly for economic reasons […]. Latakia [in Syria] already gives them a military base in the Mediterranean. They don’t need another one in Tobruk.”

That said, Russian strategists see an opportunity in Libya – partly because of Europe’s flailing policies and commitment – to repeat their Syria formula: back the strongman in exchange for diplomatic influence, military bases and lucrative contracts. With access to Benghazi port and its nearby airbase, Russia’s forces could quickly expand their presence in the central Mediterranean.

Western European states might cavil at this but show no willingness to counter it. Italy’s reopening of its embassy in Tripoli in January is hardly the stuff of a major re-engagement with Libya.

Russia’s next step could be to pressure the UN to lift the arms embargo on Libya and further weaken Sarraj’s government in Tripoli. According to Tarek Megerisi, a Libyan analyst, Russia’s current stance is ambiguous. It has voted for all resolutions in favour of Libya’s peace process at the UN Security Council and keeps open communications with several different factions on the ground, although it is dramatically stepping up its support for Haftar.

Tilting The Balance

And Russia also knows there is little backing on the ground for the UN strategy in Libya. “The idea of a unity government is a non-starter,” a young Libyan politician tells The Africa Report. “The two sides are irreconcilable.”

In Tripoli on 9 January, UN special representative Martin Kobler urged political leaders to settle their differences. “The Libyans themselves should decide whether the agreement [that created the Government of National Accord] should be amended. It’s not the business of the UN.”

Until Trump became US president on 20 January, Washington, together with Britain and Italy, backed that government and its halting efforts to restore stability. If Trump now tilts towards Haftar, in alliance with Sisi and Putin, political realities in Libya would change dramatically.

Other players have a strategic interest in Libya. The Egyptian government wants to see Libya stabilised. But Sisi’s support for Haftar firstly aims to secure Egypt’s western flank at a minimum cost.

With mounting security threats in Sinai and elsewhere at home, Sisi is not enthusiastic about sending in Egyptian troops, beyond special forces units and the odd air strike. Despite their outward similarities, Sisi has no enduring commitment to making Haftar Libya’s leader. “They want somebody on the other side of the border who can ensure stability,” a Tripoli-based analyst says.

Yet stability looks more elusive than ever. For the UAE, Qatar and Turkey, there is now a proxy war in Libya. Emirati power-broker Abu Dhabi Crown Prince Sheikh Mohammed bin Zayed al-Nahyan has supported Haftar since the general-turned-field marshal emerged as the vehicle to smash their mutual enemy, the Muslim Brotherhood. Recent LNA advances were supported by helicopter gunships, supplied by Russia, paid for by the UAE and delivered by Egypt.

While formally backing the Sarraj government in Tripoli, France has also been backing Haftar. This emerged in July 2016 when a new jihadist group, the Benghazi Defence Brigades, claimed to have shot down a helicopter carrying three members of the Direction Générale de la Sécurité Extérieure’s Service Action group. Paris said they were killed in a crash, not an attack, but President François Hollande did little to hide the fact they died supporting Haftar.

A surreal convergence of interests between Russia, France, Egypt and the US behind Haftar is now being taken more seriously. Regional experts explain how Haftar could gradually extend his influence over the whole country and squeeze opposing institutions until they fail, “opening the door for him or his backers to step in with an alternative,” as a British analyst puts it.

Haftar now controls the Sirte Basin, including its oil terminals and fields, and has an alliance of convenience with the powerful Zintanis, a group based out of Zintan that helped overthrow Gaddafi and is seen to be close to Tripoli. “If he could build a credible alliance with the south and, at the very least, maintain some kind of truce with Misrata, one could imagine him setting up an endgame,” the Briton concluded.

Haftar’s offensive helped to drive IS out of Sirte last year. He had previously overcome militias linked to the Muslim Brotherhood in Benghazi – much to the pleasure of his backers in Cairo and Abu Dhabi. Analysts question whether those that survive will continue to operate in Libya or regroup in the Sahel. The desert has long harboured seasoned jihadists like Al-Mourabitoun leader Mokhtar Belmokhtar, who was reportedly killed by French warplanes last year in Libya. Belmokhtar is thought to have survived, but with extensive injuries.

In the vast Saharan south, the Toubou ethnic group has been re-establishing its independence in the post-Gaddafi era. The Fezzan – one of the three Libyan regions along with Tripolitana and Cyrenaica – was administered by France between 1943 and 1956. France worked with the Saif Al-Nasr clan, who French sources say retain strong links to Paris.

Splintering South

Militias from Misrata and other groups of fighters are present in the south. Haftar and his deputy, military governor of the east General Abdul-Razak Al-Nadouri, have sought to project their influence in an alliance with the Toubou.

However, this “relationship is wearing thin”, a Tripoli-based source explains. Toubou politicians were not best pleased when Al-Nadouri appointed a governor in Kufra from the Zwei community. The Toubou have seen potential for more independent action: their Petroleum Facilities Guard units in the strategically important Sarir oil field have flexed their muscles by turning off the taps.

Speaking in Qatar last May, a North African politician observed that the extent of Libya’s collapse could be judged by a discreet visit to Doha of a delegation from the Fezzan region: they were seeking support for a new configuration in the south, including a possible new borderline state between Chad and Libya.

Kufra or Rebiana could serve as a capital city of a new state. Toubou leader Issa Abdel Majid Mansur suggests Toubou and other statelets could be created if Libya divides into factional cantons.

Such secession talk opens the question of whether Libya, for all the UN’s efforts, is a failed state. Such definitions “depend on the metrics used to measure failure,” says North Africa expert Porter: “If you measure it by the provision of services, then yes, Libya is already failing.”

He adds: “There is no effective sovereign government, but rather two or three rival bodies, none of whom are working effectively.” However, Porter continues, “if you measure it by the continued integrity of its borders and the continued international acceptance of Libya as a unitary state, then the answer is no.”

No leader can be certain of their power base. The Misratans are opposed to Haftar and the LNA, but are themselves divided and they will not go against each other. Even Haftar is not in full control of the LNA and has to deal with its various factions. His other problem is the disenchantment with his leadership around his base in the East, whose people have strong resentment against attempts by outsiders – such as Gadaffi or Haftar – to control them. Born into the Ferghani tribe in Sirte, Haftar is seen as a outsider by many in Benghazi and wider Cyrenaica.

Certainly Sarraj’s government in Tripoli looks weak. “The west of Libya doesn’t generally understand what is happening in the east, and the dramatic change of the narrative there,” the younger-generation Libyan politician explains.

“This is bigger than any individual […]. In the east most of the people doing the fighting are from the [Cyrenaican] Bedouin tribes […]. Politics in the east has become tribal in a way which is increasingly difficult to fit in with the idea of a Libyan state ruled mainly from Tripoli,” the British analyst adds.

“Libya is not an island,” the UN’s Kobler said on 9 January: “It has problems that are spilling into neighbouring states.” These include terrorism and migration. Last year more than 4,500 people died in the Mediterranean, trying to get from the Libyan coast to Lampedusa in Italy. Kobler argues that if Libyan leaders make the right choices and quickly, 2017 can be “the year of decisions” achieved by “peaceful dialogue not by military escalation”. Many others doubt it is possible.

Originally published in The Africa Report magazine (February 2017 issue)