Two self-made South Korean billionaires have pledged in as many weeks to give away half their fortunes –- a rarity in a country where the business is dominated by family-controlled conglomerates and charity often begins and ends at home.

Kim Beom-su, the founder of South Korea’s biggest messaging app KakaoTalk, announced this month he will donate more than half his estimated $9.6 billion assets to try to “solve social issues”.

Shortly afterward, Kim Bong-jin of food-delivery app Woowa Brothers and his wife, Bomi Sul, became the first South Koreans to sign the Giving Pledge. The philanthropic initiative was set up by Bill and Melinda Gates, alongside Warren Buffett, for billionaires to give away at least half their wealth.

Both Kims contrast with most of South Korea’s ultra-wealthy, who are largely descendants of the founders of the chaebol, the sprawling, usually family-run conglomerates that powered the country’s post-war boom and still dominate the economy.

Unlike the chaebol heirs who inherited their wealth, power, and connections, the two Kims were born to working-class families.

In his Giving Pledge statement, Kim of Woowa Brothers described his “humble beginning” on a small island.

His parents ran a small restaurant, where he slept at night, and as a teenager he gave up his dream of attending an art high school, enrolling instead in a cheaper vocational school.

Wealth, he said, had value when it was used for “the greatest benefit of the least advantaged members of society”.

Rather than keeping the entirety of their fortune, Kim and his wife said in their statement: “We are certain that this pledge is the greatest inheritance that we could provide for our children.”

Neither of the billionaire Kims has so far provided a precise timeline for their pledged donations, or detailed the recipient organisations.

Tech industry

More than 200 super-wealthy from around the world have signed the Giving Pledge, according to its website.

But it has previously been criticised for not being legally binding, and it acknowledges it is only a “moral commitment”.

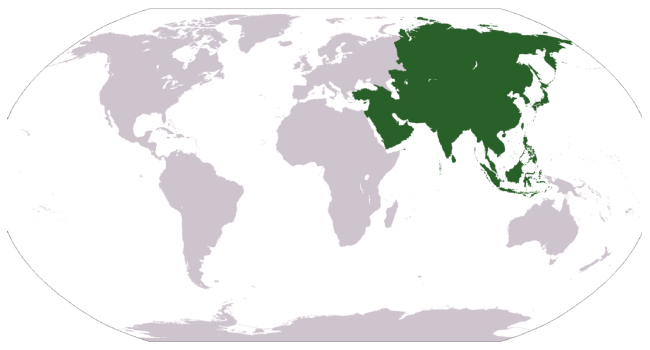

It has struggled to make headway in East Asia, listing only a handful of donors from China, Hong Kong and Taiwan, and none from Japan.

Like many East Asian societies, South Korea remains largely family-oriented, with financial ties extending well into adulthood as parents help finance higher education and housing, and little sense of obligation to give to non-relatives.

South Korea ranks 57th in the Charities Aid Foundation’s most recent World Giving Index — with Japan at 107 and China at 126.

Public philanthropy has a limited history among super-wealthy South Koreans, while the chaebols’ founding families often maintain their grip through complex webs of cross-holdings between subsidiaries.

“When the country was just reeling from the war, the priority was survival, not philanthropy, and working with your own family members was seen as the most efficient way of running a business,” Jangwoo Lee, a business administration professor at Kyungpook National University, told AFP.

But both Kim Beom-su and Kim Bong-jin have been at the forefront of South Korea’s social media and mobile tech industries boom, each founding their company in 2010 and rapidly accumulating a fortune.

Kakao’s flagship messaging application is installed on more than 90 percent of phones in the country.

Woowa owns South Korea’s biggest food delivery app, with more than 10 million monthly users — around 20 percent of the population.

The children of Kakao’s Kim have been appointed to positions in his holding company, but professor Lee said chaebol-style succession was effectively obsolete for such firms.

“Family-oriented management strategies may have worked for manufacturing businesses, but we have now entered an era where newly emerging enterprises do not really benefit from such ways,” he said.

“These are creative and unpredictable industries, and they need specialists, not family members, in leadership in order to thrive.”

That could give their owners more flexibility with their assets.

Art museum

According to the Washington-based Institute for Policy Studies, most donations under the Giving Pledge have gone to private foundations controlled by donors’ relatives, or donor-advised funds, enabling the givers to “retain significant managerial control over millions of philanthropic dollars” while generating “hefty tax reductions”.

South Korean law also offers donors some tax benefits, depending on the beneficiaries and how giving is structured.

Some chaebol families have engaged in high-profile philanthropy.

Hyundai Motor’s honorary chairman Chung Mong-Koo endowed an eponymous foundation with his personal assets and the Samsung group — South Korea’s biggest conglomerate — founded the Leeum, Samsung Museum of Art in Seoul, home to an extensive collection of antiquities and modern works.

But critics say South Korea is becoming an increasingly unequal society.

Kakao’s Kim was among those who grew up poor. Neither of his parents attended high school, and they took multiple blue-collar jobs to make ends meet, leaving him to be cared for mostly by his grandmother.

All eight members of the family shared a single room, and later he sometimes could not afford to buy lunch as a student at the prestigious Seoul National University.

Vladimir Tikhonov, professor of Korean Studies at the University of Oslo, said the South Koreans’ moves were a “display of public-mindedness on the part of the self-made rich men”.

“Meritocratic billionaires have something that rich heirs do not.”

AFP